Blaxploitation arose from the decreased censorship in 1968 as the Hays Code was replaced by the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) film rating system (Howard). With the migration of white communities into the suburbs, and big studios like Columbia, Fox, and MGM on “the verge of bankruptcy” (Howard 10), there opened an opportunity for communities left in the inner cities to show their work on a larger stage. With the Black Arts Movement asserting culture making that “should be addressed to black people in a manner that would stimulate a change in consciousness”(Godfrey 74), Blaxploitation became a place to understand black militancy, black nationalism, and black masculinity.

Black filmmakers exploited the increased policing brought on by President Nixon, the desire for more "socially conscious representations in media,"(Howard 9) and the craving for community prosperity to create a world of dominance for black men.

Through the negotiation of blackness as a man that embodied sensationalized black militant/nationalist politics, there is an introduction of caricatures for black women, queerness, and transness as one-dimensional tropes employed as ways to uplift, challenge, empower, and/or be dominated by a monolithic macho (Wlodarz).

Looking at the genre, we see black macho become a multidimensional landscape for black masculinity through the characters’ relation to the community—as a provider, tormentor, or lover—to debate the contradictions of becoming a beacon of political power within the black community. What is important to me in this space is that regardless of the explicit and formulaic approach to storytelling, these films still worked to negotiate a visual world of an empowered embodied blackness, as seen in Shaft (1971), Super Fly (1972), and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song (1971) (Howard).

As Queer Liberation and Feminist Movements gained and maintained their momentum, there was a shift around 1972–known as the Year of the Woman— towards a collective effort to highlight and catalog black women artists, create movement spaces dedicated to the experiences of women, and an increase of the number of Black women in political offices (Godfrey 110-111). With wider support for women, the stage was set for Pam Grier to begin the legacy of contemporary black womanhood that we see in traditional and new age media today through developing black heroine figures in Coffey (1973), Cleopatra Jones (1973), Foxy Brown (1974), and Sheba Baby (1975) (Poster House).

Even though having films in the genre dedicated to negotiating notions of power and womanhood was a departure from the original black macho tradition of blaxploitation, the genre actually redefined definitions of the action heroine ( Sims). However, the performances of an embodied, empowered black heroine still demanded power through an embracing of violence— either by employing it as a tactic for respect/dominance or to be gained by standing firmly in opposition to it (Tambue)— sometimes resulting in similar depictions of violence against other marginalized communities found outside of traditional modes of black radical organizing (Wlodarz).

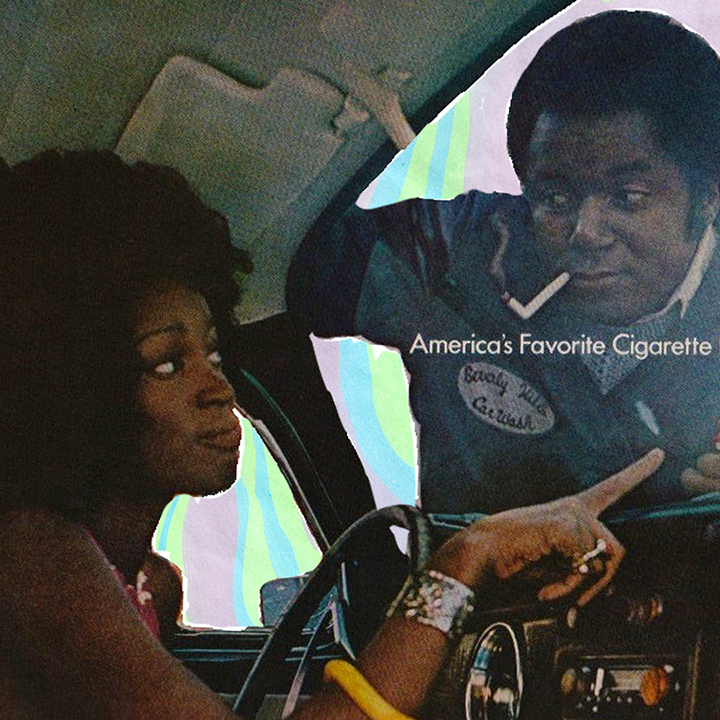

As the genre began to decrease in popularity after being openly criticized by the NAACP and CORE (Howard), we see a shift in attitudes towards Pam Grier’s lethal legacy in Friday Foster (1975), where her usually "gun-toting" (Tambue) character is armed with a camera instead, opposite a man who became a tag-a-long bodyguard. The following year, there would be the introduction of a genderqueer character in Car Wash (1976) as a part of a more egalitarian narrative structure with a cast of blaxploitation icons that challenged previous notions of queerness and their position in aiding community power-building and prosperity (Wlodarz).

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of blaxploitation as a genre that employs the same aesthetics and desire for social commentary on blackness through expanding the genre towards sci-fi, drama, and animation like Black Dynamite (2011-2015), Dolemite Is My Name (2019), They Cloned Tyrone (2023), and Cinnamon (2023) in television, film, and streaming platforms. Scholar Akinkunmi I. Oseni asserts that the resurgence in blaxploitation ideologies in movies like BlacKkKlansman (2018) and Judas and the Black Messiah (2020) are ways for reflecting on and “depict[ing] a continuum of Black resistance to anti-Black racism and social injustice” (Oseni).

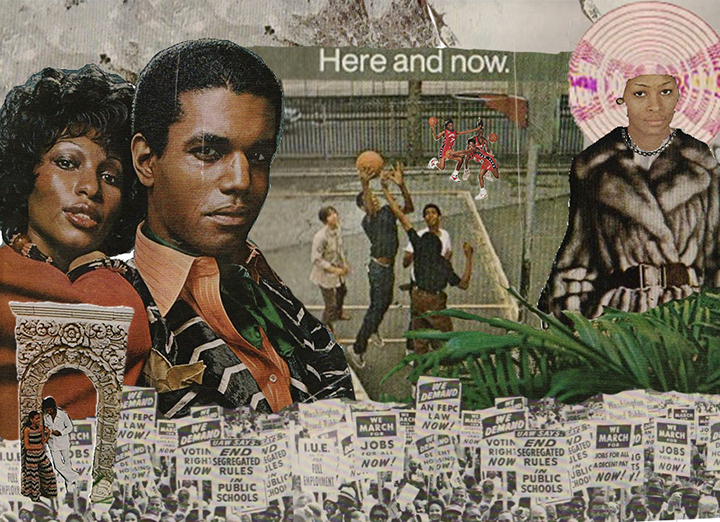

The revamping of the genre provides an opportunity for exploration and updated interrogations of black militant and nationalistic identities that can come from a more accessible filmmaking praxis that challenges contemporary ideas of black macho and black heroine tropes. With exploitation cinema in mind, my project looked to expand the ways masculinity and notions of power interacted with Feminist and LGBTQIA+ movements in the 1970s as they gained momentum by looking at Harlem from a masc black woman’s perspective.

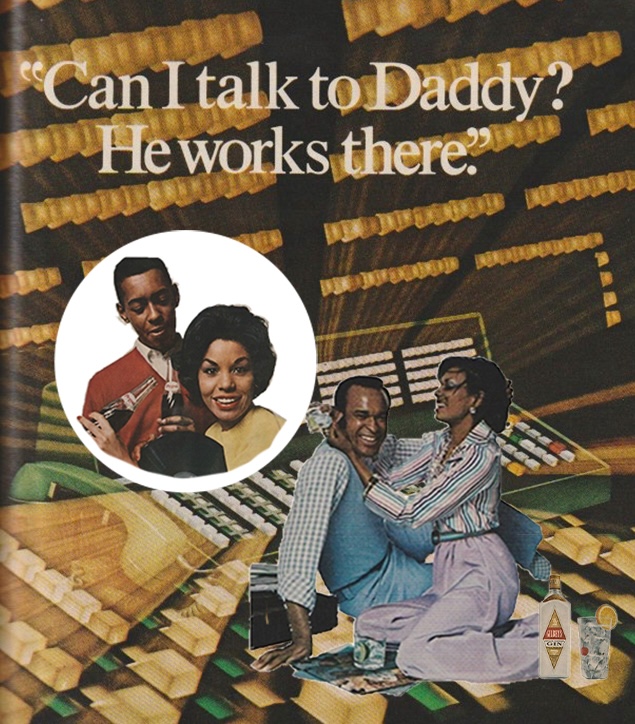

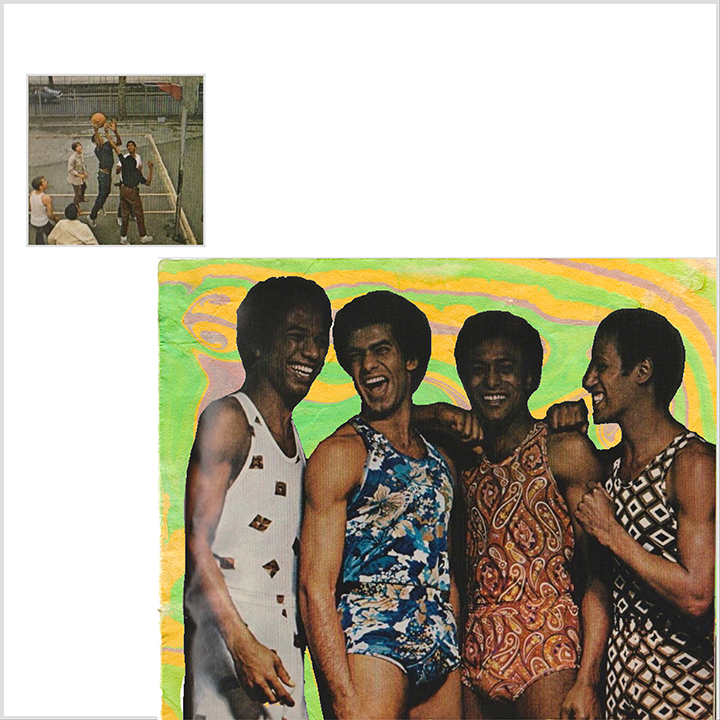

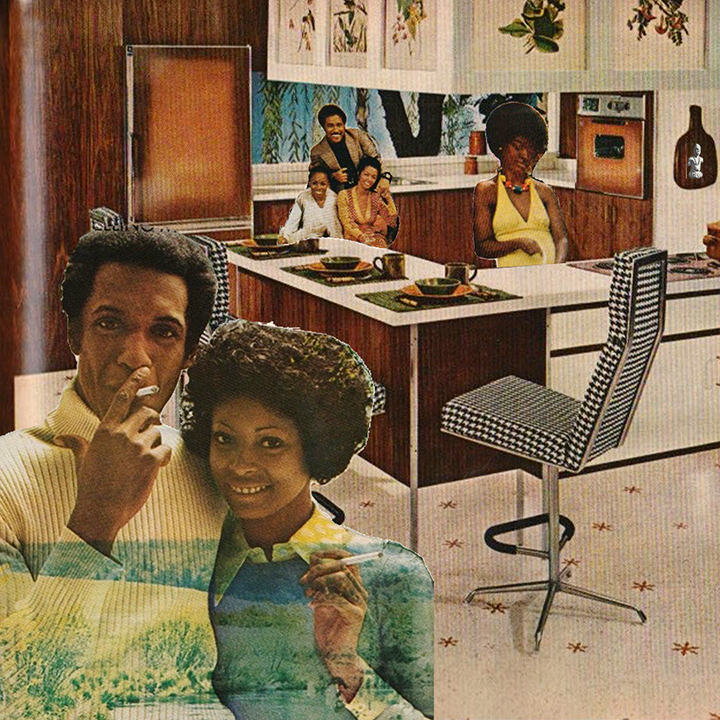

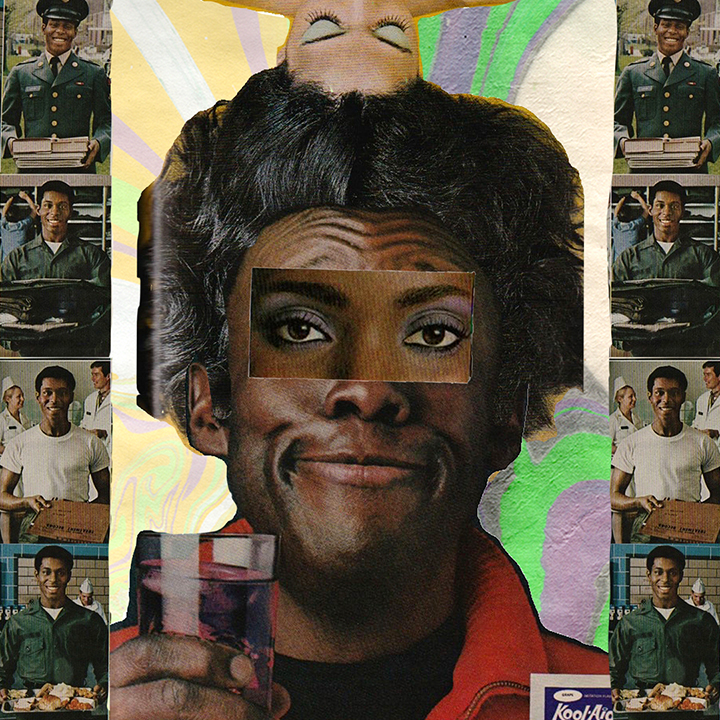

While using the Barnard Library Research Award to develop this project, I looked at photo archives from student life on campus, magazines like Ebony and The Black Scholar, more contemporary zines like My Comrade (1988), Riot Grrrl (1990), Sassy (1990s), and Shotgun Seamstress (2006) to understand the cultural landscape for debate, and audio archives like The Scholar and the Feminist VI tapes (1974-1988) to understand cadence of dialogue present in movement spaces and the ideological blind spots of political organizing at the time.

Acrylic is an animated episodic series of a 21-year-old black lesbian painter from Houston, Texas who comes to live with her cousin and uncle as she starts her degree in biology with a concentration in botany. After working a shift with her cousin at her uncle’s barbershop gets heated, she plays her cousin in a basketball game in front of the shop for his tips so she can pay for school. After beating him ends up drawing a crowd, her uncle agrees to provide her with supplies for the year in exchange for helping him start a neighborhood basketball league. As she settles into the tumultuous backdrop of 1970s New York, she learns how to navigate her newfound home with the help of her extended and chosen family.

Bibliography

Howard, Josiah. Blaxploitation Cinema : The Essential Reference Guide. Godalming, Surrey, England, Fab Press, 2020.

Godfrey, Mark Benjamin, et al. Soul of a Nation : Art in the Age of Black Power. Tate, 2017.

Lane-Steele, L. (2011). Studs and Protest-Hypermasculinity: The Tomboyism within Black Lesbian Female Masculinity. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 15(4), 480–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2011.532033

Oseni, Akinkunmi. THE RESURGENCE of BLAXPLOITATION IDEOLOGIES in CONTEMPORARY BLACK FILMS . Apr. 2023, pp. 1–57, https://etd.ohiolink.edu/acprod/odb_etd/ws/send_file/send?accession=bgsu1672959456240406&disposition=inline. Accessed 23 Jan. 2024.

Poster House. “Real Hot Girl S#!T: Black Womanhood in Blaxploitation & Beyond.” YouTube, 7 Mar. 2023, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kLh_wlFxJdY. Accessed 24 Nov. 2024.

Sims, Yvonne D. Women of Blaxploitation : How the Black Action Film Heroine Changed American Popular Culture. Jefferson, N.C., Mcfarland, 2006.

Smith, Marquita. “Afro Thunder!: Sexual Politics & Gender Inequity in the Liberation Struggles of the Black Militant Woman.” Michigan Feminist Studies, University of Michigan, 2009, https://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.ark5583.0022.104.

Tambue, Louis. “Black Women and Liberation in Blaxploitation Films.” Confluence, New York University, Gallatin School, 20 Feb. 2021, https://confluence.gallatin.nyu.edu/context/interdisciplinary-seminar/black-women-and-liberation-in-blaxploitation-films. Accessed 23 Nov. 2022.

Wlodarz, Joe. (2004). Beyond the Black Macho: Queer Blaxploitation. The Velvet Light Trap. 53. 10-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/vlt.2004.0012.